Renewable Energy

Production

Semiconductors: The Building Blocks of the Energy Transition

From wind turbines to photovoltaic cells, semiconductors are the microelectronic backbone of the energy transition. These solid materials, with their unique electrical properties, are used to adjust voltage and current from wind turbines to match grid requirements or to directly generate electricity within a solar cell. The best-known semiconductor is probably silicon, with outstanding efficiency at relatively low cost.

In photovoltaic production, quartz sand (silicon dioxide) is melted down and formed into a single crystal. This is a solid in which the atoms are arranged as evenly as possible

, explains Markus Riotte, Professor of Semiconductor Physics and Technology. The resulting block of silicon, known as an “ingot,” is then sliced into thin slices (wafers). In the PV Maritim research project, I’m particularly interested in how we can optimally integrate these wafers for their respective applications

, Riotte explains. We’re exploring solutions for embedding these thin and sensitive wafers directly into other materials. Integrated lightweight photovoltaics, for example, are suitable for land and marine vehicles, as well as for facade elements.

Lightweight Photovoltaics for Maritime Applications

Maritime transport is an incredibly exciting field for photovoltaics

, explains Riotte, Due to the reflections of sunlight on the surface of the water, even vertically mounted photovoltaic modules at sea can achieve significantly better yields than those on land.

Naturally, the modules should not weigh down the vessel unnecessarily. The biggest challenge is balancing weight and the durability of the wafers

, Riotte says. A wafer is about 200 micrometers thick, approximately twice the diameter of a human hair.

To minimize weight, Riotte is working on integrating the wafers into existing structures—for example, into the superstructure or even the wing sails of a wind-powered cargo ship. Our goal is to integrate the wafers so seamlessly that they resemble a fully painted surface both visually and functionally

, Riotte explains. This would allow the ship’s electronics to operate in port without using combustion engines or shore power cables. Ideally, we will one day see cargo ships with wing sails that have photovoltaics fully integrated

, Riotte adds. We’ve just launched a research project to make that possible.

An Alternative Material: Algae

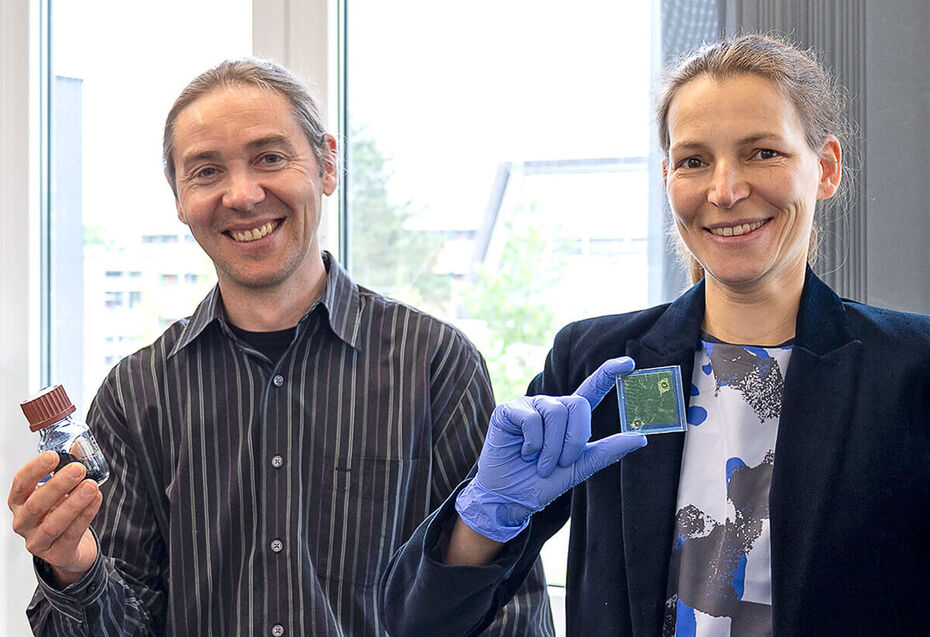

Professor Nadine Buczek heads the Laboratory for Energy Materials at TH Lübeck. Together with her colleague, Professor Mark Elbing, an expert in organic chemistry, she is working on the SolarAlgae project.

The project aims to use natural pigments extracted from microalgae to create solar cells. Currently, most solar cells are made from inorganic materials like silicon, but the production of pure silicon is energy-intensive and generates significant waste. With algae-based materials, we are exploring environmentally friendly alternatives

, Buczek explains.

First, pigments are extracted from algae and then chemically modified to improve their properties for use in dye-sensitized solar cells. The key here is that we can structure the material at a molecular level to optimize its ability to harness different wavelengths of light

, Elbing elaborates.

For us in applied science, it’s not particularly exciting to squeeze out the last percentage of efficiency from solar cells

, says Mark Elbing, who has been teaching and conducting research at TH Lübeck for seven years. Of course, from a research perspective, it is interesting to push solar cell performance as far as possible

, he adds. But what matters to us at TH Lübeck are broader questions—such as how sustainable and environmentally friendly the production process is, or which manufacturing methods are the most economical.

In their laboratories, Nadine Buczek and Mark Elbing primarily focus on establishing the fundamentals for the production of such solar cells. For implementation, we’ll need industry partners who hopefully recognize the advantages of algae-based solar cells. These benefits range from a more eco-friendly production and easier recycling to material properties like flexibility. These solar cells can be manufactured as thin films and even applied to curved surfaces

, Buczek concludes.

From Waste Heat to Electricity: The Future of Thermoelectricity with Innovative Materials

Not only algae but also waste heat can be used to generate energy. Elbing and Buczek are working together on thermoelectric generators designed to convert heat directly into electricity. We are researching materials with unique properties that have the potential to significantly increase the efficiency of thermoelectric generators

, explains Elbing. By carefully manipulating the nanostructures we can optimize electrical conductivity while reducing thermal conductivity — both of which are critical for the success of this technology

, Buczek adds.

The possible applications are many and varied: It could be incorporated into clothing to convert body heat into electricity, powering devices such as pacemakers

, Elbing suggests.

In addition, using waste heat from industrial processes holds great potential. If this waste heat could be used to generate electricity, it would represent a significant leap forward

, says Buczek. The use of these advanced thermoelectric materials in generators could open new opportunities for energy generation and contribute to the transition of thermoelectric generators from their current niche status to a more widespread application.