The Grid: Distributing and Storing

Renewable Energy

Smart Energy from A to B

Once the (renewable) electricity has been generated, it needs to be transported to consumers. Ideally, this would involve an intelligent energy system comprised of producers, consumers, storage facilities, and an interconnected grid infrastructure, all perfectly coordinated. The ultimate goal: a 100% share of renewable energy without bottlenecks or grid overloads. Professor Christian Töbermann is working on developing such smart systems.

His focus is on the grids. Energy grids are especially important because self-sufficiency would be extremely uneconomical for individual households

, explains Töbermann. Even at district level an autonomous approach is rarely effective.

This is due to a mismatch between production and consumption times. For example, if a single-family home’s photovoltaic system generates electricity in the afternoon when the family isn’t home, this only makes sense in a self-sufficient system until the storage system is full. Once storage capacity is reached, the system would have to shut down. Building a large enough storage to avoid curtailing altogether wouldn’t be cost-effective either.

If, however, we move away from self-sufficiency toward an intelligent energy system, the surplus energy generated can be directed to other consumers whose demand exceeds their own production in the afternoon. If we continue with the current national planning for photovoltaics and wind power without expanding the grid, a large share of these systems would have to be curtailed in a relatively short time.

, Töbermann notes. But expanding the grid to the point where no curtailment is needed would neither be economically or politically feasible. What’s required is a balanced approach between the expansion of generation, storage, and grid infrastructure, along with intelligent distribution and usage.

Necessary grid expansion also involves varying timelines depending on the voltage level of the grid. While low-voltage grid upgrades can be completed within months to about two years, higher voltage grid expansions require significantly more time.

This makes it all the more important to use the grid efficiently using modern IT systems. Currently, grid operations are managed to present real-time conditions in control rooms for human decision-makers. Especially in the low-voltage grids, where increasing numbers of electric vehicles and heat pumps will be connected in the future, capturing many small-scale data points will be essential. As system complexity continues to grow, automated decision-making becomes both necessary and practical

, says Töbermann.

The grid planning expert also finds the cross-sectoral view of energy grids particularly intriguing. In addition to the electrical grid, this includes the hydrogen grid and the points where the two intersect. One of the aims of the large-scale joint research project Norddeutsches Reallabor, in which Töbermann is also involved, is to develop effective solutions for such cross-sector systems and to determine which grid needs to be expanded and to what extent. This approach will allow grids to complement one another, reducing the need for every grid to be expanded to its full capacity.

Electromobility:

Charging and Storage in one Place

The Research center for Electromobility, Power Electronics, and Decentralized Energy Supply (EMLE) at TH Lübeck focuses in particular on how to integrate a charging park for electric cars into the grid as intelligently as possible. EVs are significant consumers of energy that are intermittently connected to the grid. “Electromobility is not just a question of energy generation and distribution, but above all about storage

, says Clemens Kerssen, EMLE’S spokesperson.

This issue is particularly evident in larger charging parks, for example at rest stops and service stations. When many cars charge simultaneously in a single park, it leads to power peaks on the grid because the charging stations don’t communicate with each other

, Kerssen explains. Researchers at EMLE have addressed this challenge and developed a modular, highly scalable charging park system. While ultra-fast charging is critical at highway rest stops, company charging parks might prioritize slower charging, as employees typically leave their cars idle throughout the workday.

The EMLE charging system supports both scenarios and everything in between. The charging stations communicate with one another, and a connected high-performance storage unit absorbs load spikes. This also enables ultra-fast charging. Kerssen illustrates this system in a video demonstration.

On a related note, user-centric design is vital. Ultimately, the system must integrate a transparent and flexible payment solution for consumers. With so many variables, who or what coordinates the entire operation? Artificial intelligence is indispensable here

, emphasizes Kerssen.

Hydrogen:

A new Hope for Agriculture

Agriculture is currently highly dependent on fossil resources

, says Maximilian Schüler, Professor of Environmental Sciences at TH Lübeck. Many agricultural machines are too large and heavy for battery-powered operation. However, hydrogen technology offers enormous potential to make the sector more sustainable and reduce dependence on fossil fuels. Schüler also believes that agriculture is ideally positioned to utilize renewable energy based on existing technologies.

A key challenge in agriculture is the high energy demand during harvest season, which often spans only a few days per farm and about a month nationwide. During this period, an enormous amount of energy is needed, while consumption over the rest of the year is much lower. Hydrogen storage could play a decisive role in addressing this issue. Renewable energy generated from wind and solar power throughout the year could be stored temporarily in hydrogen storage facilities and used specifically at harvest time to meet the heightened demand.

The amount of fossil energy required to produce food could be significantly reduced this way

, Schüler explains. At the same time, agriculture would become less vulnerable to fluctuating prices of renewable energy sources and could establish more stable and sustainable production conditions in the long term.

TH Lübeck: Network Hub in the Region

TH Lübeck serves as a key hub for research and knowledge transfer in the field of renewable energies. The university actively promotes the exchange between academia, industry, and municipalities, particularly within the Hansebelt region, which serves as a model region for the energy, heating and mobility transition.

One example of this collaboration is the Energie / Smart City focus area within the Hanseinnovation Matrix project. Here digital Smart City concepts are combined with the challenges of the energy transition. The region provides a strong foundation for developing innovative solutions that combine renewable energy, mobility, and infrastructure. A key issue is the successful implementation of intelligent systems in a Smart City, with a particular focus on integrating renewable energies into existing infrastructures.

As part of CONBAU Nord, TH Lübeck - together with the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für zeitgemäßes Bauen (ARGE), IB.SH and the NordBau Trade Fair - is also driving forward the heat transition in residential construction. As part of the Baukongress, it brings together experts from across sectors to discuss practice-oriented solutions for the building and energy industries, viewing complex topics from multiple perspectives. The heating transition is both local and personal, yet it is closely interlinked with the transformation of the entire energy infrastructure. Its successful implementation requires coordinated initiatives, informed decisions, and bold action from all stakeholders—from building owners and planners to administrators, builders, and energy providers

, explains Professor Sebastian Fiedler, the project’s initiator.

As part of the joint research project Norddeutsches Reallabor (NRL), TH Lübeck is testing ways to achieve climate neutrality by transforming energy-intensive sectors, particularly in industry and mobility. More than 50 partners from business, science, and politics are working together to develop sustainable innovations and strengthen Northern Germany as an industrial hub. By leveraging hydrogen technology and waste heat recovery, the NRL aims to reduce CO₂ emissions by 75% by 2035 and serve as a model for sector coupling in Germany and Europe.

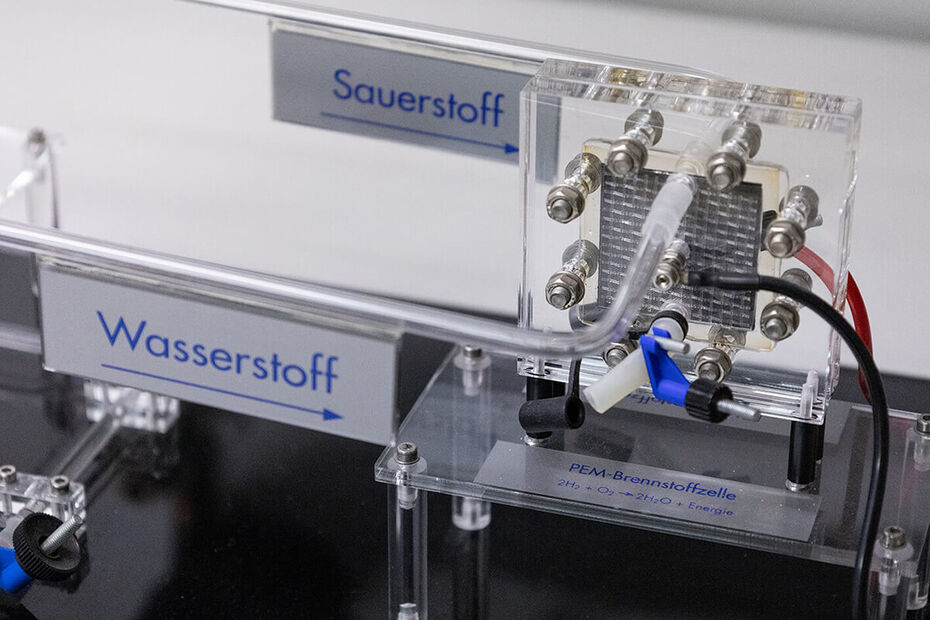

The state of Schleswig-Holstein is likewise committed to hydrogen technology: It aims to play a leading role in the hydrogen economy and promotes the creation of a regional network. TH Lübeck is part of this hydrogen research community, known as hy.sh. This involvement extends to education: the university has acquired a dedicated hydrogen system that allows students to gain practical experience in all aspects of hydrogen production and utilization.

The Energy Transition in the Building Sector

The building sector accounts for over 30% of final energy consumption in Germany, making it a critical component of the energy transition. In new construction, there are now many ways to reduce energy consumption right from the design stage. Renewable energy sources, such as rooftop photovoltaic systems (PV) or heat pumps that utilize environmental heat, can also be used. What is the challenge then? Reducing energy consumption in existing buildings is a major challenge. The majority of energy consumption in the building sector today comes from existing buildings in cities, neighborhoods, and standalone properties

, says Dirk Schwede, Professor of Energy and Building Engineering in the Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering at TH Lübeck.

What are the solutions? Key to the energy transition are, first, the energy retrofit of buildings to reduce final energy consumption, and second, the climate-neutral supply of energy in the form of electricity and heat from renewable sources. It’s essential to develop balanced and economically viable renovation strategies for both individual buildings and across neighborhoods that can be practically implemented under local technical and socio-economic conditions. The current funding landscape for energy-efficient renovations also plays a critical role

, Schwede notes. Organizational questions are equally important: How do you renovate occupied buildings?

Common technical questions include: Is the heating system suitable for a heat pump?

or Will there be a climate-neutral district heating supply in the future?

Professor Dirk Schwede both researches and teaches these approaches at TH Lübeck. He is an internationally sought-after expert on energy-efficient, climate-friendly, and sustainable buildings. In this role, he connects with networks locally and globally. One local example is the Community of Practice: In the Community of Practice (CoP), we bring together stakeholders working on the energy transition in the building sector from the Lübeck region to discuss relevant topics and foster exchange between different groups

, Schwede explains.

Digital Building Models as Key to Saving Energy

It’s not just new constructions that are relevant: many existing buildings will not undergo any fundamental renovations by the target year for climate neutrality, but must still make their contribution. This contribution will not come in the form of energy-efficient renovation, but rather through building operations optimization and user engagement. To unlock this potential, an interdisciplinary research team at TH Lübeck launched a project called Digital Infrastructure for Sustainable Building Operations (DING) heißt es.

As part of this project, typical existing buildings used for teaching, research, and administration on the TH Lübeck campus are being closely examined. The goal is to collect and share data that enables researchers to study how building usage impacts energy consumption and supply. Based on this data, the team develops further strategies to reduce energy consumption and increase the use of renewable energy. The project involves collaboration between four subject areas from the departments of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, and Applied Natural Sciences.

Investments have been made in modern stationary and mobile measurement technologies, including sensors for indoor air, windows, heating, and lighting, as well as meters for heat and electricity consumption. Sensors to monitor building usage and weather conditions have also been implemented. In addition, digital models of the buildings have been created that contain all the information needed for simulations to develop innovative operational strategies. DING allows us to carry out comprehensive research projects focused on optimizing building operations and engaging users while testing innovative approaches and methods in a real-world laboratory

, explains project leader Professor Sebastian Fiedler, highlighting the value and sustainability of the project.

Simulating for a More Efficient Energy Transition

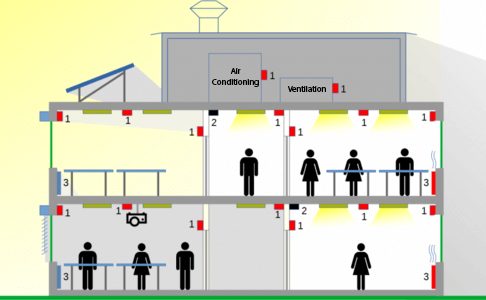

Animation of building ventilation. Source: Christian Blatt

Simulating for a More Efficient Energy Transition

The data collected in the DING project can be used to feed building simulations. Often, it’s not immediately clear which energy measure is most promising for a given building, because building design and building systems must work in harmony.

Christian Blatt, Professor of Building Simulation and Optimization, explains: The beauty of a building simulation is that you can visualize what you are doing. You can compare many different scenarios and identify the best solution.

For instance, simulations can display different thermal layers inside the building, indicate the temperature at varying heights, and show how air circulates throughout the building. This makes it possible to determine the ideal number, height, and size of windows, the placement of ventilation systems, and which technical systems would be most suitable.

While new construction typically begins with well-defined parameters, work on existing buildings begins with gathering the necessary information: Are the original blueprints still accurate? How thick are the walls? Which materials were used? What is typical for buildings of that era and region? In some cases, measurements have to be taken on site. The goal is a detailed room database, that serves as basis for the simulation. With that data, you can reconstruct the building from the ground up

, says Blatt. Then you can begin to simulate and optimize systems, like heating.

A frequent concern is to avoid overheating and improve summer thermal protection. Large glass surfaces are particularly tricky. You have to consider how far you can go with passive ventilation concepts and shading, or whether you need air conditioning - otherwise you can quickly end up with 50°C (122°F) indoors

, Blatt notes.

Particularly Suited for the Exceptional

According to Blatt, simulations are currently especially worthwhile for unique, high-profile buildings, such as museums. Another compelling

application are complex factories, where internal conditions like machine waste heat and similar influences must be considered in addition to external factors like solar radiation.

Blatt is also keenly interested in historic buildings. Owners of such properties often ask valid questions, such as whether a heat pump would be economically viable and, if so, how it should be configured. Other common inquiries involve photovoltaic systems or solar thermal energy, particularly in the context of heritage conservation regulations. The more unique a building is, the more prone to error the standard approach, which relies on predefined calculation tables, becomes. I’m convinced that in 10 years, simulations will be the norm for many buildings, at least in higher-end segments

, says Blatt. One day, I’d also like to launch a research project focused on standard buildings, where results can be broadly applied from one structure to another. I believe there’s still a lot of potential, as building simulation can prevent costly mistakes and significantly reduce costs.

Proactive Heating Solutions

Once the decision for a heating system has been made, Ulf Lezius comes into play. Heat pumps, for example, operate most efficiently when they run steadily over extended periods, rather than being forced to deliver large bursts of heat during sudden cold spells. That’s why Lezius is developing a system that integrates weather forecasts, heating systems, and digital building models, such as those produced by the DING project. This system enables automated, predictive heating while optimizing it for the specific usage of each room. If a movie theater is primarily used in the evening, an algorithm calculates when the heat pump should start before a temperature drop, and at what intensity it should run, to efficiently achieve the desired temperature on time. To make this work, the system collects real-time data every 15 minutes from the building, the weather forecasts, the room scheduling plans, and actual room occupancy. A simulation then determines which heating strategy is the most effective.

These optimizations are especially important for large heat pumps in district heating networks. In the future, the system could also incorporate data from electricity production. If there is an abundance of low-cost, renewable wind energy on the grid, for instance, this could significantly influence the simulation results and heating strategy. Lezius is confident: We need smart strategies for forecasting, regulating, and managing energy systems.

Energy-Efficient, Sustainable Construction Abroad

The building sector is a major driver of sustainable transformation not only in Germany but worldwide. Globally, it contributes substantially to greenhouse gas emissions, resource consumption in the form of building materials, land use, and waste generation. At the same time, the built environment provides the framework for comfortable, high-quality living.

Professor Dirk Schwede, who has previously worked as a researcher and consulting engineer in Australia, Asia, and the Middle East, is involved in various projects focusing on sustainable construction abroad. In the BMBF-funded project Climate-Adapted Material Research for the Socioeconomic Context in Vietnam (CAMaRSEC) a large consortium of scientists from Germany and Vietnam investigated the use of sustainable building materials for tropical climates in Vietnam. In another BMBF-funded project, Resource-Efficient Construction with Sustainable Building Materials (ReBuMat) interdisciplinary networking among researchers and practitioners to promote the use of sustainable materials.

Professor Schwede’s work in the sustainable development and transformation of the construction and building sector in other countries is part of technical development cooperation projects. Key topics include energy-efficient heating, cooling, and ventilation of buildings, resource-efficient construction, and life cycle assessment of buildings. These projects also focus on developing evaluation and financing instruments for sustainable buildings and neighborhoods, tailored to countries at different stages of development in their construction industries.